Green with Eevee

The world was shorted a version of Pokémon Green. This can be corrected with obsessive madness.

Nearly all of Pokémon’s main entries has enjoyed enormous international success. Nearly. But not all of the original Game Boy releases made it outside of Japan. The question of which one didn’t has a messy answer. The games originally released in Japan in 1996 as Pocket Monsters: Red and Green. Towards the end of that year, the success of the initial releases instigated the release of a special third version, Pocket Monsters: Blue, first available through mail order before getting a broader release the next year. (I’ll refer to this version as “Japanese Blue” to distinguish it from international releases.)

The initial releases of Red and Green were immensely popular, of course, but they had a number of issues — some of them were bugs, and some of them more objective, like some awkward-looking sprites — and Japanese Blue addressed some of the outstanding bugs, and refreshed the look of every Pokémon. And, accordingly with how Red and Green each had exclusive Pokémon to promote trading between the games, Japanese Blue had its own distinct list of encounters — none being exclusive to the title — as well as a different set of in-game trades.

When it came to exporting these games, Game Freak (or maybe publisher Nintendo, who knows) made a few decisions. One, because of its improvements, Japanese Blue was used as the base for the localized game, with the encounter tables from Red and Green implemented for their respective versions. And two, they decided to recast Green as Blue, feeling that red and blue would be a more appealing pair of colors for an American audience. The answer to the question, then, of what versions we ended up getting, is muddled. We got the bones of Japanese Blue with a splashing of Red and Green paint. Like some half-baked Ship of Theseus, in a certain sense we didn’t get any version that Japan did. Well, except Yellow.

But in my heart, the bottom line is that we don’t have a Pokémon Green. And as someone whose favorite color is green, that has always felt like a slight. So, say you’re a dork who wants to put some kind of synthesis version of a localized Green together, for your own misguided version of what you’d call “satisfaction.” (To distinguish this version of Green from the authentic Japanese Green, I’ll refer to this hypothetical version as “Pseudo-Green.” I’m sorry if that’s obnoxious, but it’s the best I can do.) What would that game look like?

One vision is this: a ROM hack that alters an English version of Blue to reimplement the graphics, mechanical differences, and bugs of the original Japanese release, called Pokémon Green In English. This is an interesting effort. Without going through all the patch’s details with a fine-toothed comb, this likely feels very close to how the original Red and Green did. But of course it does, because the games we got feel that way anyway. But they changed so many small details — slight graphical differences on the Town Map, or the fact that if you lose against Sabrina the game considers you to have won — that I’ll take on faith that they covered everything even remotely noticeable.1

If you want something that feels more like a genuine third version, though, perhaps you’d also want to alter the encounter tables to reflect Japanese Blue’s. This is what I did. I used a utility called RBY Wild Pokémon Editor,2 and, referencing a Google Sheet someone put together, manually changed the encounters in every area to be identical to those in Japanese Blue.

Here’s where I got a little obsessive. As mentioned, Japanese Blue had its own set of in-game trades. These are Pokémon acquired by trading with NPCs found throughout the game. So these trades have to be altered, too. And because these Pokémon have been given nicknames, you have to figure out what to call them in English. It would seem you’d have to either do your best to translate the Japanese nicknames, or just make something up. But we’ve lucked out, here. In the 2020 Nintendo data leak popularly called the Gigaleak, localization files found in the source code for the original games indicated that the Japanese Blue Pokémon had, for reasons unknown, been given localized names.3 So, using a different utility called TradeEdit GB, these are what I used for my own home-baked Green.

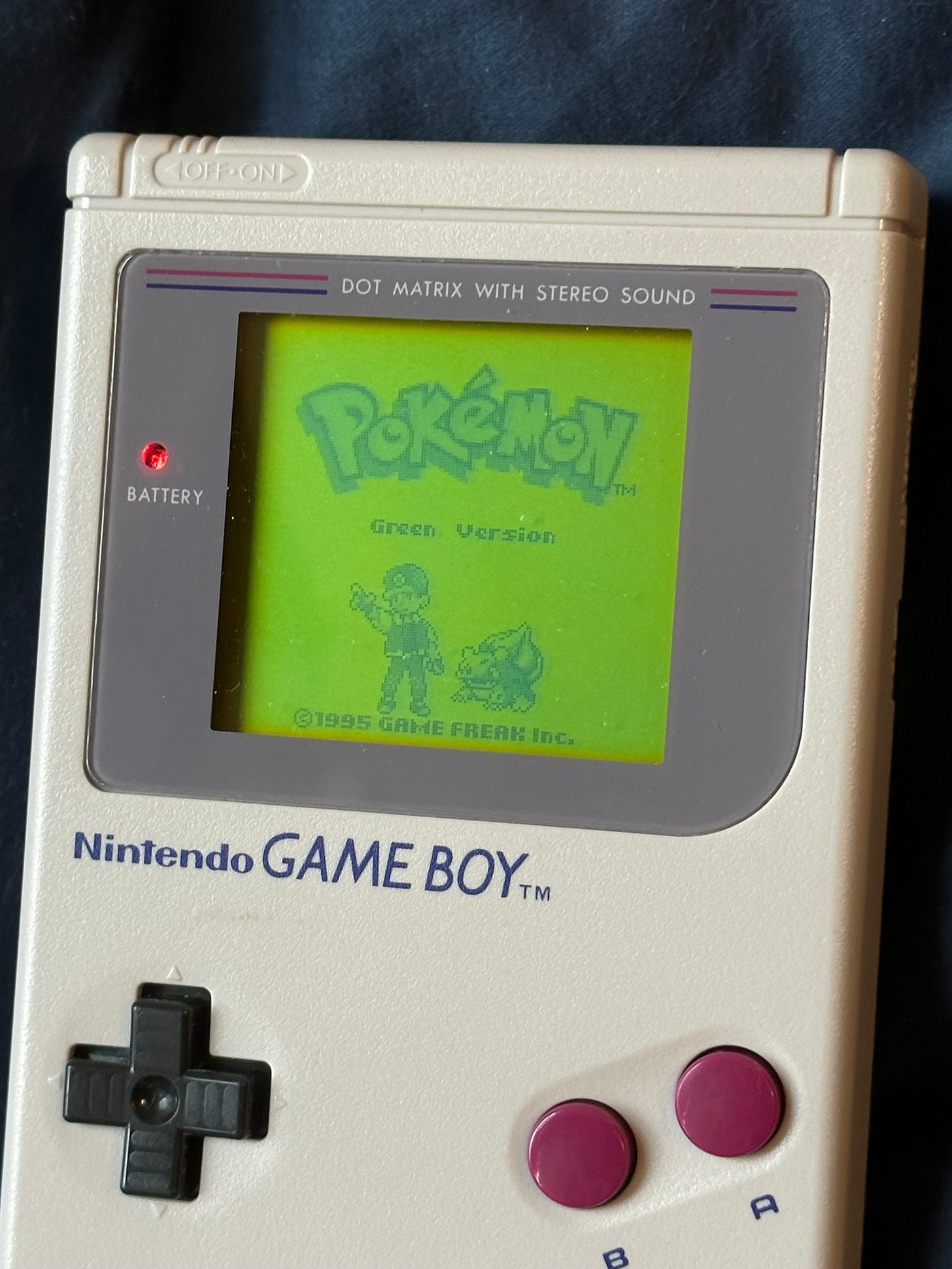

Once you have all the changes in place, you end up with about as satisfying a Pseudo-Green as can be managed. Or, at least, you have its ROM. But wouldn’t a green cart be lovely…?

This is a more complicated issue than you might expect, given how common bootleg Pokémon carts are. There are usually quality issues with these, but that’s not what I’m talking about. When I first got a high-quality flash cart for my version of Pseudo-Green, I was confused to find that on naming screens, the symbol for ending name entry, normally reading “ED,” was instead a garbled sprite. This happened on whatever authentic hardware (or FPGA equivalent) I tried, but not when the ROM ran through an emulator. What was happening?

I found the answer unexpectedly. Pokémon Stadium is a Nintendo 64 game where you can battle using your team imported from a Game Boy cart, by connecting it to your controller with the Transfer Pak. And a YouTube video demonstrated that the American version of the game could detect, and use, a fan-patched Green cart, even though we never saw any version of Green here.

There’s a caveat mentioned in the description, however:

Most of the features work, but the game crashes at the GB Tower due to Pokémon Stadium not having a rom of Pokémon Green.

The original Pokémon Stadium had a feature where you could play your Game Boy Pokémon game, with fast-forward options, if you had it plugged into the Transfer Pak. The trick is that the game isn’t actually running from your cart; the official ROMs are all built into Pokémon Stadium, and only the save data on your cart is read and written. However, in Pokémon Stadium 2, the integration works differently.

Also, the GB Tower even works, since it seems with Stadium 2, its GB Tower actually downloads the rom through the Transfer Pak, so I show a bit of the Pokémon Green romhack.

But a viewer comment on the video observed that their own copy of a hacked Green could not be downloaded. The culprit isn’t obvious. They had used a cart with the MBC5 mapper, and the original English Pokémon games were made with MBC3 carts instead. Now, bear with me, because I don’t have a lot of technical knowledge in this area: a mapper, as far as I understand it, is a type of chip a game cartridge uses to grant extra capabilities to the hardware, often related to game size, graphics, or sound, and for Pokémon allowed for large save files in order to store hundreds of captured Pokémon.4 The details here aren’t too important (I think), but at any rate, because Stadium 2 is looking for a particular kind of cart, using a different one results in failure, even though the architecture of the two mappers is not radically different.

The fine details on all of this elude me. But I asked the commenter about the garbled name entry symbol, and he confirmed that it happened on his cart as well. By the way, having casually run into two people who have English Green carts of their own, this quest in making one for myself feels a little less quixotic.

The process is nonetheless becoming a debacle. For the most “authentic” experience, you have to go out of your way to find, specifically, an MBC3 cart, both to fix a very minor visual bug, and to ham it up in a Nintendo 64 game where I would almost never care to use the downloading feature. But I did do it. I had to buy one at a relatively silly price from a specialist,5 but I did it. And after flashing it, I did in fact use it to fuss around with Pokémon Stadium 2, if only to prove a point.

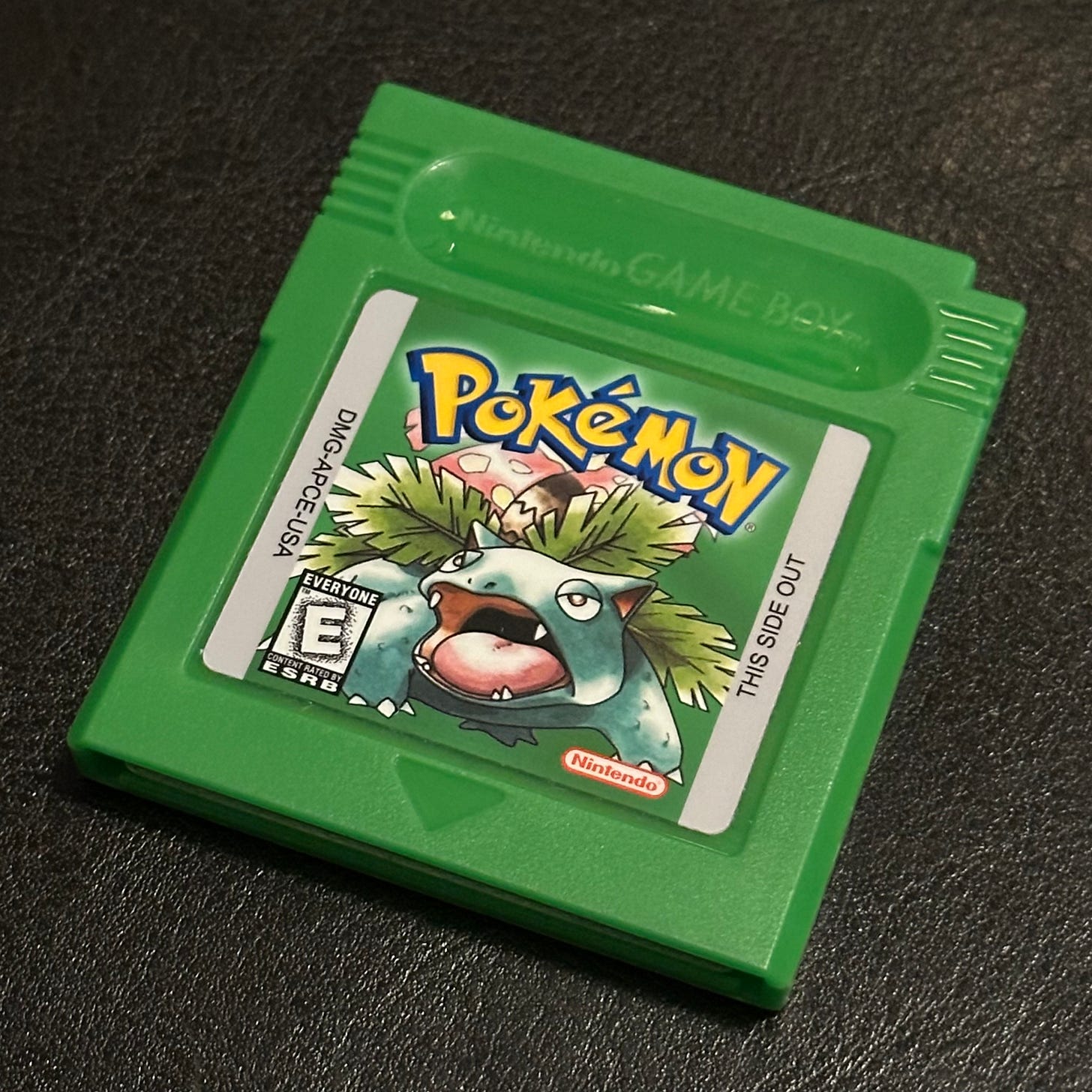

To complete the Pseudo-Green package, you need a green cart shell to house the chipboard, and a good label to match. The cart shell isn’t too hard to find (although I can’t remember where I ordered it from), but if you’re being particular about looking authentic, you have to mind where the hole for the screw is, because it’s toward the bottom on real Game Boy carts, and square in the middle on many bootlegs. If you’re not careful matching the housing to the board, you might not be able to put the thing together at all. As for the label, I got mine from Retro Game Cases. It’s a good-looking, high quality decal with accurate colors. There are some subtleties that reveal it’s not a genuine label (besides the fact that it’s for a game that doesn’t exist), such as its satiny finish, but the business isn’t making these labels to deceive people — in fact, for games that do exist, the labels make clear that they’re reproductions, likely to deter people from using them to falsely sell bootleg games, or authentic games in bad condition.

So, am I proud of myself? Maybe a little bit. It took more work than I would have expected to put together everything I wanted into a new third version for the first Pokémon games. It’s not at all an accurate version of what an official Green would have looked like here, of course: no company would realistically have any interest in putting out a buggy mess after they’d released the version that fixes things up. But I guess I like the option of playing the inversion of the Japanese releases because, through a convoluted process of addition and subtraction, I’ve gotten the full English experience of the Japanese games without playing a completely faithful version of any of them. As stupid as the methodology is, it’s just enough for my brain to accept as the best I can hope to get.6

Actually, there are some bugs in the localized versions of the game that weren’t in the original. The best known of these is the old man glitch, which is the easiest (but not the only) way to encounter MissingNo. and other problematic Pokémon. At any rate, such bugs are gone with this patch, although I’m guessing that they were fixed deliberately rather than caused by any actual reversion of the code to its original state.

As I was writing this article, romhacking.net announced that it was winding things down. As far as I can tell, this mainly means that it won’t be hosting any new projects from now on, acting only as a news hub. I don’t know what that means for some of the projects already hosted there, including the ones linked to here.

These names, along with quite a lot of other information, can be found here at The Cutting Room Floor.

The NES is a good platform to examine to understand the influence of mappers. For example, the first Super Mario Bros. is just about as complex as a game can be for that system without mappers, whereas the mapper for a game like Super Mario Bros. 3 enables some powerful effects, such as the ability for the screen to scroll diagonally. Mappers also allow for larger ROM sizes through bank switching: only 32KiB of memory can be accessed by the Game Boy CPU at a time, but a mapper enables it to access memory banks beyond the current position. This process can also be used for save RAM, if the game has an awful lot of data to save. With regard to the Game Boy Pokémon games, this is what allows the player to store many Pokémon in boxes on the PC, but because of the bank switching involved, the game has to be saved every time the current box is changed. This has other side effects. One is that when playing using save states, there is a risk that, on loading a state, all stored Pokémon that aren’t in the currently selected box will go up in smoke. Some of this I gleaned from niwanetwork.org, and the rest I’m just vaguely remembering.

I got it from a store called Timville. The price is only silly when weighed against the relative worth of this project, and not against the expertise that went into creating the flash cart. Tim is also a swell guy and sent me an extra flash cart when he made a minor error in my order. Thanks, Tim!

Except that I actually have played through Pocket Monsters: Green.